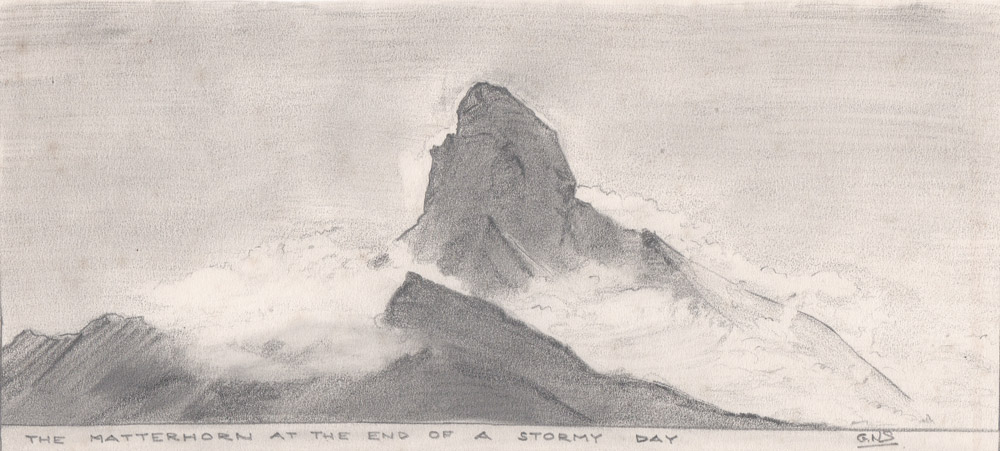

When my mother was dying of cancer in 1965, the very last birthday present she gave me and my twin brother John was a new ‘centenary’ edition of Edward Whymper’s classic mountaineering book, Scrambles Amongst the Alps, telling the story of the dramatic first ascent (and calamitous descent) of the Matterhorn, which was a very remarkable feat for 1865.

My mother had been to Zermatt in her youth with her parents and had been enchanted by it. She talked about the Matterhorn as something very special, almost magical – as if it were a kind of symbol of life itself which was being so cruelly taken from her. My father’s plan was that, if she survived, we would all go to Zermatt as somewhere for her to convalesce. It was a sadly hopeless fantasy; but when she died in the spring of the following year, my father took John and me to Zermatt, together with my aunt, my mother’s sister, in her place and our three cousins.

I am fairly certain that I would never have become a climber if it had not been for that sad chain of family of circumstances. Once I’d read Whymper’s classic book I became completely obsessed by the Matterhorn, and when I first saw it on a perfect summer Alpine day in August 1966 it surpassed all my expectations. It filled my imagination. John and I were very keen to climb it, and were very disappointed to be told by the guides that we couldn’t, because they had a rule that you had to be 18, and we were only 16. We nevertheless had a wonderful walking and climbing holiday. We were very much ‘taken under the wing’ of a splendid old guide, Emil Perren, and it was with him that we did our first ever rock climb, on the Riffelhorn, together with my father, aunt and cousins and two other guides. I think because Emil knew of my obsession with the Matterhorn history he deliberately arranged that one of those guides should be Viktor Taugwalder, a distant relative of the Taugwalders who had been with Whymper on the first ascent of the Matterhorn.

When we all sat on the top of Riffelhorn that August day in 1966, John and I knew that climbing would now be an important part of our lives. Our cousins did not catch the bug, partly because of other interests.

The following week, Dad and aunt Hazel climbed the Matterhorn while we did a much easier climb (the Furggrat frontier ridge). We finished at the Hornli hut where we waited for Dad and Aunt Hazel to return from the Matterhorn.

One of the first to descend was a very distinguished looking grey-haired gentleman. We got talking and his guide said proudly, ‘He is the great nephew of Edward Whymper’. Apparently he had wanted to climb the Matterhorn all his life. He was in his early 60s, looked very fit, and had found it quite easy. He duly gave me his signature.

We finished the holiday by climbing our first 4,000-metre peak, the Breithorn, which although very easy was an absolutely magnificent viewpoint of all the Pennine Alps.

The holiday had gone so well that the next year Dad took John and me back to Zermatt. By this time we’d taken up rock climbing and were far more capable. Apart from climbing all over the Riffelhorn, first with Emil Perren, and then doing our first leading, we climbed our first really good alpine peak, the Zinalrothorn (4221m). Once again this was organised by Emil Perren, and to make it very special for us he chose for our guide Heinrich Taugwalder, the great great great? grandson of Old Peter Taugwalder, who’d been with Whymper on the first ascent of the Matterhorn.

Although the weather in the early hours of the morning was very misty, and the barometer had dropped, Heinrich decided to go ahead. The ascent went very smoothly, and was very dramatic in the conditions with the nearby summits of the Pennine giants, the Matterhorn, Dent Blanche and Weisshorn, looming in and out of the cloud. It had a superb knife-edge summit ridge, with huge exposure over the near-vertical east face.

The summit itself was one of the finest I’ve ever encountered, with a small, nearly flat top: it was like standing on a dining room table in space, with none of the rest of the mountain visible below, and just the huge summits of the Weisshorn and the Matterhorn poking up on either side through the clouds. Heinrich took a summit photograph of us:

And this brings me round, full circle, to pay tribute not only to Heinrich, but to the whole Taugwalder family, on this 150th anniversary of the first ascent of the Matterhorn.

Heinrich was one of the very finest guides I have ever climbed with (I have climbed with six), and he was very encouraging to John and me on that first major alpine route.

It should be emphasised that the Taugwalders were the only Swiss guides in the early 1860s who believed that the Matterhorn was possible – the only others who thought its legendary inaccessibility could be breached were the Italian guide Carrel and the French guide Croz.

There is not space here to add much about the first ascent of the Matterhorn on July 14th 1865, and the famous disaster on the descent. The truth is that the blame for the accident should really be shared between four of the seven members of the party. First, the very experienced Rev. Hudson and Edward Whymper, for deciding to combine their two parties with no clear plan and no single leader; Rev. Hudson in particular for deciding that the 19-year-old novice Douglas Hadow, who had only climbed one other mountain – the very easy Mont Blanc, would be capable of coping with something as technically demanding as the Matterhorn. Whymper and Hudson, again, for not sticking to their original plan of placing a fixed line (which would probably have saved them) on the very serious traverse on to the north face to safeguard their descent (even though Old Peter Taugwalder had the safety line in his sack). Whymper for dallying on the summit of the Matterhorn with the Taugwalders to finish a sketch and not fully concentrating on the seriousness of the descent they faced. They caught up with the other four members of the party just above the most serious and difficult part of the descent. The problem with this was that, when the experienced English alpinist, Lord Francis Douglas, who was at the back of the front party, turned and expressed his wishes to Whymper that they should join up as one single rope of seven climbers – because he feared he might not be able to hold the party if anyone slipped – they made THE fatal mistake of using the thin line rather than the remaining full-weight rope, which Young Peter (right at the back of the party) was carrying. Whymper, again, is primarily to blame here for not overseeing this operation properly, because it is clear that Old Peter was not familiar with the superior strength of the spare heavy weight rope that his son was carrying, which Whymper had brought out from London that summer.

But the seeds of the disaster did not stop there. Inexplicably, the immensely strong and experienced guide of the front party, the Frenchman Michel Croz, took up a position at the front, rather than following what was already the standard procedure, even in those early days of alpinism, of the strongest member of the party coming down last as anchorman. Again inexplicably, the immensely strong and experienced Rev Hudson placed himself third on the rope, leaving the much lighter and less experienced Lord Alfred Douglas at the back. (The order, once they had re-roped as a single party of seven, obviously should have been: Douglas, Hadow, Hudson, Croz, Whymper, Old Peter, Young Peter.)

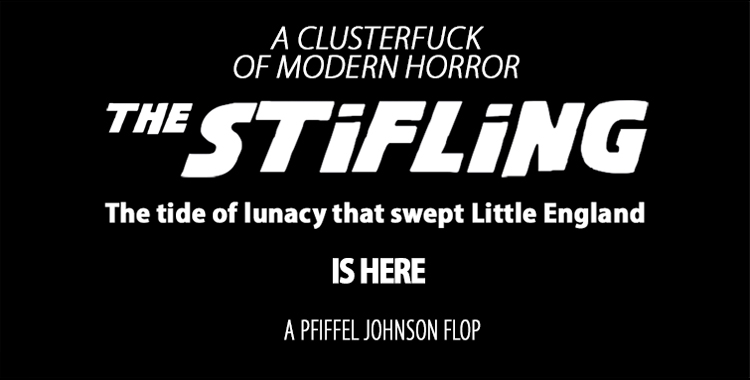

(More details of exactly what happened may be found in the meticulous scholarly study, The First Descent of the Matterhorn by Alan Lyall, Gomer Press,1997)

(More details of exactly what happened may be found in the meticulous scholarly study, The First Descent of the Matterhorn by Alan Lyall, Gomer Press,1997)

In the terrible event, at the hardest and most insecure part of the climb, a steep rock bulge with poor sloping holds, Hadow slipped and fell onto Croz; their weight on the rope snatched Hudson and Douglas in turn from their holds, at which moment Old Peter Taugwalder, with lightning reflexes, got the rope between him Douglas over a knob of rock so that when the rope came tight he held, but the very thin line stretched like elastic and snapped at mid-point, and the four leading climbers plunged nearly four thousand feet down the north face to their deaths.

There then followed an extremely harrowing descent for Whymper and the Taugwalders, it taking them several hours in their very shaken condition to regain the relative safety of the Hornli Ridge.

When the three survivors finally walked into Zermatt the following morning like ashen ghosts, Seiler, the owner of the Monte Rosa Hotel, was waiting at the doorway. Grim-faced Whymper passed him without a word. When Seiler asked what was the matter, he turned and said just six words that have gone down as one of the most famous utterances in mountaineering history:

‘The Taugwalders and I have returned.’

When John and I returned to Zermatt from the Zinalrothorn with Heinrich Taugwalder 101 years later, Dad took us all, with Emil Perren, to dinner at the Monte Rosa Hotel. At the end of the meal, Dad said he wanted to settle up the guiding bill. He looked at it for a few seconds in puzzlement.

‘But, Emil, this is far too little.’

Emil replied simply: ‘They are twins. Two for the price of one!’

It was a deeply touching moment, partly because Emil knew very well the reason we’d come to Zermatt in the first place the previous year.

Unfortunately, I was never able to visit Zermatt again, and so was never able to see either Emil Perren or Heinrich Taugwalder again. Today I want to pay tribute to those two very fine Zermatt guides.

The reader may also be interested in a more recent blog I have written (September 2018) about ‘The Second Ascent of the Matterhorn‘.